Sparkle Street Press

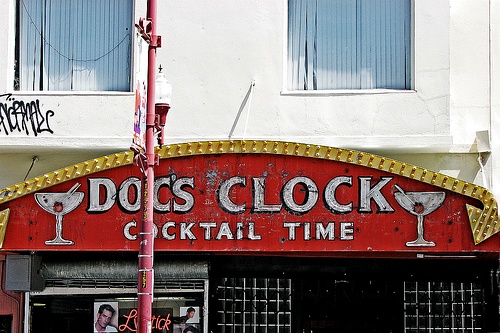

Doc’s Clock

Doc’s Clock was a good place to get out of afternoon’s flare-up, when the sun over Mission Street was blazing toward some painful equipoise between day and night, and hung in a shaft through the transom and the open doors, and lit the linoleum floor tiles there, and lived, for an hour, in the varnish of the near end of the bar, and in a glass of beer halfway down, and in an ashtray in the dark, suggesting by inference the farther reaches of the room.

Down back, someone left the men’s room and came knocking through the tables, past the shuffleboard machine, a guy in a white cowboy hat, along the bar, beat-up drunk. He veered into a barstool and spun off toward the street, and stood there in his plaid Western shirt, getting his bearings in the light before choosing a direction and moving on. The bartender, a woman I didn’t know, came out of the dark, took his glass and empty and wiped the bar. She dropped the bottle in the recycling and asked what she could get me. I was killing an hour after work while my wife packed some things at home. She was moving to her sister’s place while I figured out what I was doing with a woman in Los Angeles.

I reached for a napkin. I could never just sit. I started writing a few things down, just to be doing something. Even apart from my circumstances the drink made me nervous, as a first drink always did at that hour, as though something were about to happen, as though I were engaging some impossibly greater force, fate for instance, or maybe it was the hour, happy hour, the witching hour, or maybe it was my situation after all. I sipped my drink, a whiskey on the rocks, and described my surroundings, the sunlight that, now, dazzled the backbar and frescoed a patch of the wall, and pretty soon it turned into a letter to the woman in LA. A couple of bearded kids came in and I put them in the letter. One of them called the bartender Amanda.

I’d flipped the napkin over and covered half the other side with writing when a woman in office clothes blew in and took a stool across the curve of the bar from me. I put her in. She asked Amanda if there was a payphone she could use to page someone. Amanda said the bar’s phone was a rotary phone but she could use a payphone across the street and page someone to the bar. The woman went through her bag. She was in a flurry. One of the bearded guys offered her his cell, and she paged someone to the number at Doc’s. Then she thanked the guy and ordered a vodka with a twist. He put his phone away and resumed his conversation. They were talking about movies. I wrote, “Wherever you go, the only thing people are talking about is movies.”

When the woman got her drink she pulled a big red hardcover book from her bag and started reading it. She flipped pages forward and back. She had her book and the guys had their movies and I had my letter, and we all had our drinks, and we were balanced there, floating on the moments in a nice equilibrium.

Then the phone rang and she was off her seat. She left us wobbling there and ran down to take it. Amanda was talking into the phone.

Amanda asked if there was a Mike.

I slipped off my stool and walked down. The woman was coming back. I told her I wouldn’t be long.

I took the phone. My wife was calling to say she was leaving now. I talked with her for a minute and walked back to my seat.

I summed all this up in my letter to the woman in LA. She was married too. The night before, her husband had announced he was moving out and wanted a divorce.

The woman across from me said, “That fucking piece of shit.”

I looked up. It had just escaped her. I wrote it down.

She drained her vodka and kept pretending to read her book, or genuinely trying to read it to distract herself. She was visibly upset now, squirming around on her stool, pushing a hand through her hair. I got another napkin, and from then on it was all happening as I wrote, as though I were creating it.

She was off her stool by the time I heard the phone ring. Amanda said “Mike?” and held the receiver in the air. I avoided the woman’s eyes as I walked on down.

It was the woman in LA. I told her I was leaving soon and I’d call her from home. Back on my perch, I picked up the cigarette I’d left smoking on the bar. The woman across from me was barely keeping it together. Her face would collapse toward tears, and then she’d take a breath. She rubbed her right leg, forcing her concentration on the page.

She let out a ragged sigh. She drained the icewater dregs of her drink. Then she clapped her book shut, stuffed it in her bag, and walked out.

We watched her go.

The phone rang. I sat up. Of course it would ring the moment she left. I saw the whole tableau unfolding from a bird’s-eye view of the tricks and slights of fate. Amanda gestured with the receiver toward the end of the bar. I ran outside into the sun. The woman was in a crowd at the corner, waiting to cross. I ran up the block, dodging people, fixed on her there with her headphones as she gathered herself forward into the empty evening. She stepped off the curb and I touched her elbow and said, “The phone! The phone’s for you!”

She stalked past me toward the bar. She was free now to get it off her chest, and she marched along, relieved and cursing.

I trotted behind her saying “Aah, he probably tried to call while I was on the phone.”

She said, “I’m sorry. It’s been going on a long time, y’know?”

I followed her in. It was okay now, for someone, for tonight anyway. Amanda and the two guys were standing at attention. They’d been watching the doorway.

One of the guys said, “It’s for you, guy. I think it’s for you.”

I turned as she whirled out, and I followed, making silly helpless apologies as she looked to the left, to the right, and moved off.

I watched her go for a minute. Then I walked back through the bar and picked up the phone. It was my wife again, calling to tell me one last thing.