Sparkle Street Press

Northern Ohio Live, April 1984 – The Movies

In the months before the nationwide premiere of Harry and Son on Friday, March 3rd, two of the movie’s three principals immersed themselves in the rituals surrounding the release of a major motion picture. Paul Newman—star, director, co-producer, and co-author of the screenplay—ventured from his home in Westport, Connecticut, to tout the production on television talk shows. The former Shaker Heights High School actor believed so strongly in Harry and Son that he had agreed to take the lead role as a condition of obtaining financing from Orion Pictures, despite his own choice of Gene Hackman to play the cantankerous construction worker. Ronald Buck, attorney and restaurateur turned screen writer, holed up in Malibu, California, to await reviews of his first labors as co-producer and co-author. For Buck, March 3rd would mark the end of a twelve-year struggle to get Harry and Son on the screen.

Only Raymond DeCapite, who works three days a week at a state liquor store near his home in Euclid, remained unperturbed by the impending public reaction to Harry and Son and uninvolved in plans to help get it off to a strong start at the box office. DeCapite, ultimately, had as large a personal stake in the movie as Buck and Newman, since the inspiration for Harry and Son was DeCapite’s own 1961 novel, A Lost King.

On March 3rd, an hour before DeCapite and his wife, Sally, left for Euclid’s Lake Theatre to catch the opening-night screening of Harry and Son, an old friend interrupted their dinner–an everyday dinner of linguine with homemade tomato sauce–with a prediction. “Raymond,” he said, “you’re going to have to wait until they’re clearing the popcorn boxes out of the theater to see your name on the screen.” Actually, a perfunctory acknowledgment of Harry and Son’s indebtedness to A Lost King was what DeCapite had been expecting and even hoping for. Months before the premiere of the film, his own reading of a copy of the screenplay sent to him by Buck had shown him that the movie would probably bear only a passing resemblance to his novel. And because of that, DeCapite had ruled out a chance for A Lost King to be reissued for potentially lucrative sales as a paperback.

“The offer was from a publishing firm in London, and the book would’ve been reissued under the title Harry and Son, not A Lost King. I refused. It would’ve been wrong, misrepresentative. You should never do anything just for money,” said DeCapite as Sally drove the few miles from their apartment on Knuth Avenue to the Lake Theatre. “So I’m on the phone with this literary agent in London, explaining my position. ‘Mr. Dee-cap-i-tay,” he says—pronouncing my name better than any of my relatives do—‘Mr. Dee-Cap-i-tay, you have made me very cross.’ He later wrote to Bertha Klausner, my agent in New York, to say that he respected my decision, although he didn’t understand it.”

“Anyway,” the fifty-nine-year-old DeCapite deadpanned, making a minute adjustment to the tweed cap that partially covered his shock of white hair, “what put an end to the deal was the fact that they wanted Paul Newman’s face on the cover. I wanted mine.”

Although he considers himself a teller of stories that take the form of novels (his first, The Coming of Fabrizze, came out in 1959 and was widely praised) and plays, DeCapite is an ardent fan of American cinema. A Lost King is the first of his stories to have been adapted for film, but because Ron Buck was keen to try his hand at writing, DeCapite did not contribute to the script. He is no stranger to the inexplicable permutations a screenplay can undergo, however. “James Agee, who was one of the best writers this country ever produced, and certainly one of the best critics, wrote the screenplay for The African Queen [released in 1951], yet John Huston, who was directing, brought in someone to rework Agee’s script,” DeCapite said as Sally pulled into the theater parking lot. “Agee ended up with the screen credit, although, in a sense, the script was no longer his.”

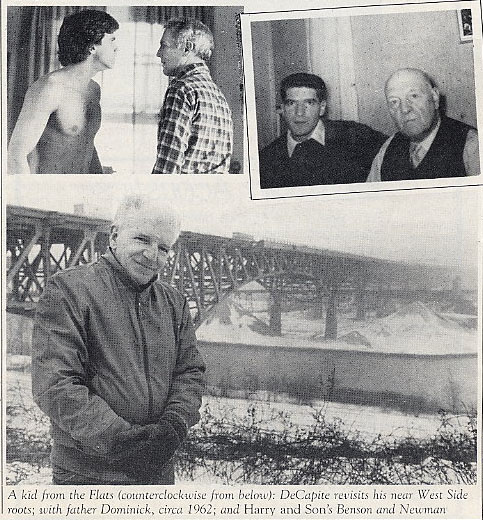

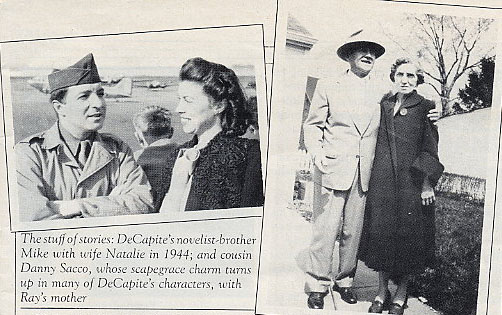

DeCapite’s knowledge of this particular writer’s nightmare came from his brother, Michael, who was James Agee’s friend and was in part responsible for the existence of Harry and Son. Nine years Ray’s senior, Michael distilled the experience of a youth spent at West 14th Street and Fairfield Avenue-—the edge of Cleveland’s industrial Flats—-into an acclaimed first novel entitled Maria, an account of Italian-American family life that is still recommended reading for college sociology majors. Two other novels, No Bright Banner and The Bennett Place, followed before Michael DeCapite’s death in 1957 at the age of forty-one. “Michael,” according to Ray, “would have accomplished extraordinary things. His work was moving in unusual directions.” Michael’s legacies to his brother were his demonstration that the writer’s life was hard but possible and his profound interest in the world of their shared upbringing, a world of churches and coffeehouses, of leisurely front-porch conversations on summer evenings-—a world of stories told and retold. In A Lost King, Ray, who “started writing seriously” after graduation from Western Reserve College in 1952, mined the same rich vein Michael had in Maria, and the result was a story as evocative of place as anything by Saul Bellow about the city of Chicago. From reading the screenplay, DeCapite already knew that Buck and Newman had shifted the locale of Harry and Son from Northern Ohio to Florida; that much of the world of A Lost King was gone. He was curious to see whether the movie had managed to preserve any of the contentious, loving, often funny relationship between father and son that is at the center of his novel.

“Look how crowded it is,” remarked Sally as she angled the DeCapites’ car into a parking space behind the theater. “I bet it’s all family.” Her joke had a basis in reality. The whole clan turned out for the two plays DeCapite had had produced in Northern Ohio-—Things Left Standing and Sparky and Company, which won the Cleveland Critics Circle Award in 1980 and went on to a production at New York City’s Il Teatro Rinacimento, which presents works by and about Italian-Americans. (DeCapite’s third and most recently completed play, Where The Trains Go, has so far been produced only in Boston.) True to form, the sparse audience at the movie was dotted with DeCapite’s family and friends (“Pardon me, are you Mr. DeCapite? Only kidding, Ray.”)

“Well, you have to admit, he is gorgeous,” Sally said as Harry and Son’s opening scene revealed an impossibly youthful looking sixty-year-old Newman. As the DeCapites sat and watched a film that altered A Lost King nearly beyond recognition, all their remarks were similarly complimentary, polite, and even charitable (“That’s a nice shot, isn’t it?” “Very dramatic.”) They were watching the culmination of twenty-two years of talk about what a great movie A Lost King would make-—talk by television director Peter Baldwin, who purchased the first option to adapt the novel for the screen in 1962 and who later tried to interest Italian director Vittorio De Sica in the project; by Los Angeles musician Vincent D’Onofrio, who mortgaged his home in a failed attempt to raise a production budget; and finally by Ron Buck, who heard about the novel from Marlon Brando’s sister, Jocelyn. “I knew as soon as I had read it that I wanted to try making a movie out of the book,” said Buck. “I thought it was wonderful—the character of the son especially.”

The story that captured the imaginations of Baldwin, D’Onofrio and Buck is an old one: A young man takes his first steps toward knowledge of self and the world beyond his home, in the process confronting and challenging a father whose values differ greatly. What makes A Lost King much more than a mass of generation-gap clichés are its sharply observed characters: the father, an Italian immigrant bereft of a beloved wife and stripped of physical strength by illness, who rages against life; and his son, a sweet-natured goof of a kid with a capacity for enjoyment of life sorely lacking in his father.

“Strictly speaking, the story isn’t autobiographical. However,” DeCapite smiled slightly, “I was comfortable in using a first-person narrative in the book, so I guess that says something. Most people assumed I was writing about my father, Dominick, who came to this country at the age of sixteen. That wasn’t absolutely true, although there were things in that character that were also in my father-—the harshness, for example. My father was a very stern man, very strict and particular. As for the character of the son, well, his work experience was like mine. I had a lot of jobs in my time. When I was young, I didn’t know what the hell I wanted to do.”

Harry and Son changes much more than the locale of A Lost King. New characters have been added to supply romantic and erotic interest, and emphasis has shifted from the son to the father–radical alterations that were necessary, according to Buck, because “I didn’t feel that Ray’s book was going to make it commercially.” Tilting the balance of the movie still further in the direction of the father are the performances: Newman steamrollers the goofy Robby Benson (“a Hershey Bar left out in the sun,” as one of DeCapite’s cousins dismissed him) in the role of Harry’s son, Howard. Even more fundamental, however is the difference in texture between DeCapite’s novel and the film. The anger and urban grittiness of A Lost King have been replaced with upbeat insights fresh off the greeting-card rack, played out against a background of sun and surf. The end of DeCapite’s novel finds the character of Paul alone in the world but in possession of a level of self-awareness and strength he had lacked before; the last scene of Harry and Son shows Howard with a ready-made family, a career as a writer and a laid-back demeanor that suggest he found them all while strolling through a shopping mall.

As the gulf between A Lost King and Harry and Son became increasingly obvious, dismay and worry about Ray’s reaction settled over the opening-night assembly of friends and relatives, most of whom had read the novel as a matter of course. When DeCapite, exhibiting signs of restlessness, at one point got up and walked to the back of the theater, his Aunt Rose Clement elbowed her daughter Rosemary Terango. “Sweet Jesus,” she whispered. “Ray’s leaving!” As it turned out, DeCapite was only looking for the men’s room. He returned in plenty of time to see fulfilled the prophecy made by his friend earlier in the evening. With the high-school ushers who tidy the Lake Theatre to keep them company, Ray and Sally watched the screen intently. Finally, at the very end of the credits appeared the line: “Suggested by the novel A Lost King by Raymond DeCapite.”

Afterward, a small group gathered around the DeCapites in the theater lobby, debating the suitability of the movie’s ending and offering what congratulations they could. “I thought it showed relationships very well,” a friend of the family hedged. Someone suggested a round of drinks at the nearby Emerald Room by way of an impromptu opening-night party. “The Emerald Room? In Euclid?” asked Sally. “Is that in the Hotel Revco?”

Seated in a draft near the door of the bar (which turned out to be called the Emerald Isle) and nursing a boilermaker, DeCapite found himself surrounded by women, a situation he frankly enjoyed. “The women in my life,” he said, “have been sensational.” In particular, he meant Sally, a secretary at the Cleveland Clinic; his sister Marie DeCapite (“always there in the clutch”), principal of William Rainey Harper Elementary School in Cleveland; and his cousin Rosemary Terango.

“Let’s go to my house,” Terango suggested as conversation became difficult above the din of rock music. “I’ll make coffee.” Once at the table in Terango’s cheerful red and white kitchen, DeCapite relaxed and voiced his thoughts freely. Terango served coffee, bread, sweet red peppers cooked in olive oil and a shot glass of Canadian Club, which she, Ray and Sally sipped communally.

“For the last three or four weeks,” said Ray, “friends have been telling me, ‘I saw Paul Newman on TV,’ or ‘I saw Robby Benson on TV, talking about Harry and Son.’ If they had asked my advice, it would have been: ‘Don’t release it. Just keep talking about it.’ That way, it would have become an American myth. I have to think of the movie as apart from the novel, since they were so different. But even allowing for that, I thought it was pretty bad.”

“Was it?” asked Terango’s husband, John, who had just gotten home from work. “Good. I voted for it to be bad.”

“There weren’t enough scenes where people really talk to each other,” DeCapite said.

Talking to each other is what characters in DeCapite’s novels and plays do best and most frequently, and little wonder: DeCapite has a storehouse of family tales–and relatives who are adept at retelling them–for inspiration. A number of these revolve around his eighty-four-year-old cousin, Danny Sacco, whose scapegrace charm figures prominently in the characters of Sparky in Sparky and Company, Paul in A Lost King, and although unsuccessfully realized, Howard in Harry and Son.

“Things just happen to Danny,” said DeCapite of the man who once held a job dusting desks at a government office in downtown Cleveland. Like Paul’s in A Lost King, Sacco’s exuberance has often been displayed with a fine disregard for consequences. He was especially fond, when visiting Ray’s grandmother, of picking her up and whirling her over his head, oblivious to the fact that she considered such displays highly undignified. One day she cured Sacco of his impudence by whacking him on the head with a shoe she had somehow managed to take off in the midst of an aerial tour of her kitchen. Rosemary, who had listened with a grin to what was clearly an oft-told tale, interrupted Ray with one of her own. “After the opening performance of Sparky and Company, Danny came up to me. ‘That kid,’ he said, meaning Raymond, ‘is always telling stories about me. I wouldn’t mind, except that he tells them wrong. I’m gonna get a lawyer.’”

Storytellers like DeCapite, who chart the courses of the human heart, have fallen on hard times. In the United States, film and publishing industries alike have shown increasing reluctance to invest in anything but potential blockbusters, which accounts for Ron Buck’s inability to find backing for Harry and Son – even with commitments from actors like Henry Fonda, Jason Robards and Anthony Quinn–until Newman agreed to play the lead. Fonda, Robards and Quinn were simply not viewed as “bankable” in the same way that Newman was. Despite the fact that his two published novels received a great deal of critical praise, DeCapite may well face an analogous problem in finding a publisher for his recently completed novel, Pat the Lion on the Head, which has as its setting Cleveland’s West Side Market. “My agent gave the manuscript to a reader–someone who is paid to evaluate works of fiction,” he said. “The reader’s comment was, ‘This is writing of a very high order, but it has no commercial potential.’”

“In this life,” DeCapite had said earlier in the evening, “we don’t need luck as much as stamina.” If that is true, then DeCapite has all the stamina he needs–composed of equal parts intelligence, humor and grace under pressure–to shrug off disappointments like Harry and Son. Expect to hear more from Ray DeCapite. After all, he has many more stories to tell.

Roberta Hubbard is a contributing editor of LIVE.